以下两段节选自 Olivia Laing 的 The Lonely City 的第五章 The Realms of the Unreal。

Lonely child vs. healthy child

在 20 世纪初的阶段里,为了照顾到婴儿的身体健康,人们忽视了婴儿的心理健康,这反倒让婴儿更脆弱。

这次新型冠状病毒(COVID-2019)在中国肆虐了一个月并逐步得到控制,却又在海外大肆蔓延。算到现在,病毒已经连续轰击我们的精神有两个月之久。在纽约亲历这次 COVID-2019 在席卷于美国大地的阶段,在家中努力做到 social-distancing,但读到这里不免会让我再一次想到关于身体和心理健康的有趣关系。

This sounds like common sense, but at the time of Darger’s childhood the consensus among health care providers of all kinds – from psychoanalysts to hospital doctors – was that all children required in the way of nourishment was a germ-free environment and a ready supply of food. The reigning belief was that tenderness and physical affection were actively detrimental to development and could in fact ruin a child.

To modern ears, this seems insane, but it was driven by a genuine desire to improve child survival. In the nineteenth century, child mortality had been enormously high, especially in institutions like hospitals and orphanages. Once germ transmission was understood, the preferred strategy of care was to maintain hygiene by minimising physical contact, moving beds apart and limiting interactions with parents, staff and other patients as much as possible. While this did indeed successfully reduce the spread of disease, it also had an unexpected consequence, which took decades to be properly understood.

In the newly sterile conditions, children failed to thrive. They were physically more healthy, and yet they wasted away, particularly the infants. Isolated and untouched, they went through paroxysms of grief, rage and despair, before eventually submitting passively to their state. Stiff, polite, apathetic and emotionally withdrawn, their behaviour made them easy to neglect, further entrenching them in acute, unspeakable loneliness and isolation.

The art of collage

拼贴(collage)是我一直以来难以抓住的艺术手法。这一段从「拼合修补精神分裂者的心灵碎片」的角度阐释了「拼贴」这种艺术手法的复杂的、符号化的、脆弱的美。

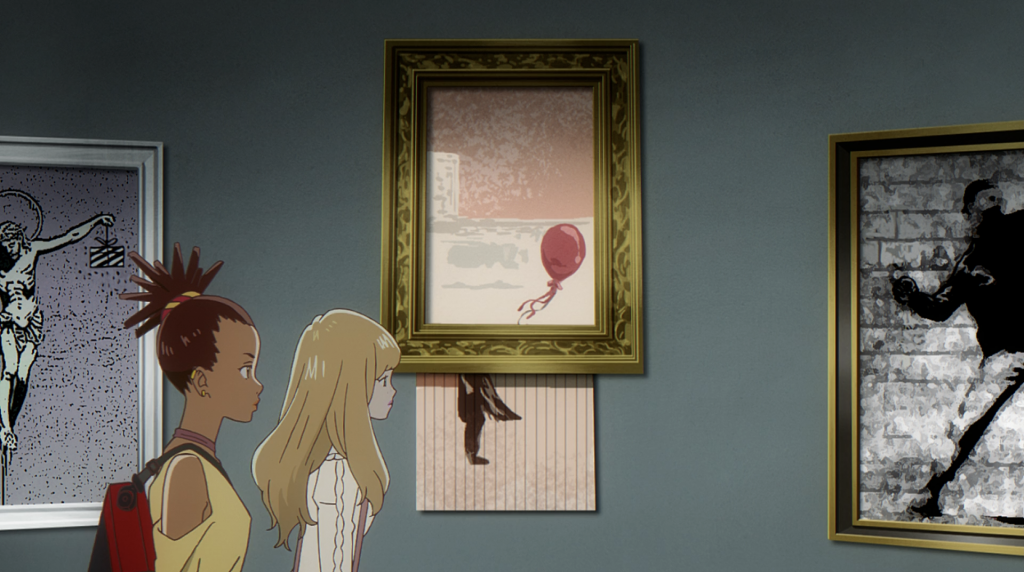

Loneliness here is a longing not just for acceptance but also for integration. It arises out of an understanding, however deeply buried or defended against, that the self has been broken into fragments, some of which are missing, cast out into the world. But how do you put the broken pieces back together? Isn’t that where art comes in (yes, says Klein), and in particular the art of collage, the repetitive task, day by day and year by year, of soldering torn or sundered images together?

I was thinking a lot at the time about glue, how it functions as a material. Glue is powerful. It holds fragile structures together and stops things getting lost. It allows the depiction of images that are illicit or hard to access, like the homemade pornography David Wojnarowicz used to make as a child from Archie cartoons, taking a razor and turning Jughead’s nose into a penis; that sort of thing. Later, he used to wheatpaste discarded supermarket ads on walls and hoardings in the East Village, on to which he’d spray-painted stencils of his own design, making his visions adhere to the skin of the city, its outward shell. Later still, he worked intensely with collage, bringing together disparate images – fragments of maps, pictures of animals and flowers, scenes from pornographic magazines, scraps of text, the haloed head of Jean Cocteau – to construct the complicated and densely symbolic paintings of his maturity.

Like Wojnarowicz, they understood the rebellious power of glue, the way it lets you reconstruct the world. […]